Source Also see: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35

My Feelings on this!!!

He is a freedom fighter, fighting the American Empire's invasion of Iraq.

Just because I am an American doesn't mean I agree with the illegal unconstitutional wars the American government gets involved in.

I also find it a little ridiculous charging Ahmed Alahmedalabdaloklah with Federal crimes in Arizona simply because the Microchip PIC l6F84A chip is manufactured in Arizona.

If you ask me Ahmed Alahmedalabdaloklah should be treated as a POW or Prisoner or War. Not a criminal.

Anybody with some basic electronic skills can do this

While that may be true, any person who knows a little about making electrical circuits can easily make one of these devices that the Iraqi Freedom fighters are using to detonate bombs or IEDs aimed at the invading Americans.

All it takes is an LM567C DTMF decoder chip which can be purchased for $1.50 from any electronics parts store. This chip decodes the DTMF tones and feeds them to the computer chip.

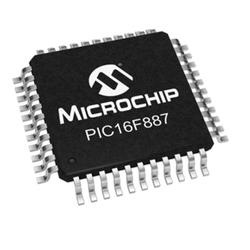

A Microchip PIC l6F84A chip which can also be purchased for under $5. This is a dirt cheep computer chip which is used to fire the IED when fed the right commands.

And last but not least you would need a 10 cent transistor to fire off the IED.

The FBI saying that Ahmed Alahmedalabdaloklah is the only person on the planet who is smart enough to make these firing devices is ridiculous.

The Phoenix New Times and the FBI describe Ahmed Alahmedalabdaloklah as an electrical genius.

While that may be true, any person who knows a little about making electrical circuits can easily make one of these devices that the Iraqi Freedom fighters are using to detonate bombs or IEDs aimed at the invading Americans.

All it takes is an LM567C DTMF decoder chip which can be purchased for $1.50 from any electronics parts store like TriTek or Circuit Specialists. This chip decodes the DTMF tones and feeds them to the Microchip PIC l6F84A computer chip.

The Microchip PIC l6F84A chip can also be purchased for under $5.

This is a dirt cheep computer chip which is used to fire the IED when fed the right commands.

You might want a 2705 voltage regulator chip which will put out a nice clean 5 volts to run the whole circuit. I think you can run the PIC l6F84A at 3 volts, so a voltage regulator chip that puts out 3 volts would be needed instead of the 2705.

And last but not least you would need a 10 cent transistor to fire off the IED.

While most assembly languages take a few days or even weeks to learn, the Microchip PIC assembly language is one that you can pick up in a few hours and become reasonably good at.

I suspect that the Iraqi and Afghanistan freedom fighters are not making the equipment to transmit the signal to detonate the bombs or IEDS.

They are probably just using existing cell phones. In the US you can buy a TRAC cell phone for $10 and activate it for another $10 for a total of $20. And that sounds a lot cheaper than making your own device to tell the bomb to go off.

You would use this cell phone to dial the cell phone connected to the IED and set it off.

And on the bomb or IED side, they are probably just using an existing cell phone for the device to explode the bomb. Again spending $20 for the cell phone is probably a lot cheaper than building it yourself.

Then to get the bomb working they attached the LM567C DTMF decoder chip to the speaker of the cell phone. Or probably just throw the speaker away and replace it with the LM567C DTMF decoder chip.

The LM567C DTMF decoder chip then takes any DTMF signals that it receives from the cell phone and sends them as a binary number to the Microchip PIC l6F84A computer chip.

You probably could run the circuit by attaching it directly to the cell phone's battery. You might need a voltage regulator chip if the battery voltage is too high. Like a 2705 chip which I use all the time to reduce a 9 volt battery down to 5 volts.

The Microchip PIC l6F84A computer chip is then programmed to look for a sequence of DTMF numbers to tell it to explode the bomb or IED.

So you could then use a sequence of digits such as

*911#to tell the Microchip PIC l6F84A chip that you want the bomb to explode.

And then the Microchip PIC l6F84A chip would turn on one of it's ports.

The ports only handle a few milliamps, so you would have to use a transistor to increase that from a few milliamps to enough current to fire a blasting cap and explode the bomb or IED.

If you wanted to get real creative you could use the Microchip PIC l6F84A computer chip to fire off the bomb in a number of other ways.

One way would be for it to simply activate the bomb, so that it could be fired by some other sensor. Such as a motion detector to detect humans. Or a device to detect magnetic fields so you could have it fire when a vehicle like a Humvee or tank comes near it.

Or you could use it say to activate the IED or bomb so it goes off at a set time. I guess that would be a way to prevent it from accidently going off while it was being planted.

Years ago I build a similar device.

I read an article about some guy whose parents were conned by TV peacher into giving them all their money.

The guy build a circuit to call the preacher's 800 number constantly, wait for an answer, and then hang up. His goal was to drive up the preachers phone bill with thousands of calls to his 800 number.

I build a similar device.

I hard coded the phone number to dial into a memory chip. I don't remember how I did that.

I used a 555 timer chip to cycle thru and dial each of the digits in the phone number.

I then used a 5589 DTMF encoder to generate a DTMF tone from a binary number. And I placed that DTMF tone on the telephone line.

And once all the digits were dialed the telephone company would dial the call.

I think I used a second timer chip to hang up the phone and start a new call after some set amount of time.

I thought it might be fun to change the phone number to 911 and then attach the device to a pay phone and have it constantly dial 911. But I never did.

I disagree 100% with the Phoenix New Times and the FBI calling Ahmed Alahmedalabdaloklah a terrorist.

He is a freedom fighter, fighting the American Empire's invasion of Iraq. Not a criminal.

Yes, when you are looking at the output pins on microprocessors they don't let you use much current. I think you on a Microchip PIC l6F84A chip you are limited to 25 milliamps on the output ports

So if the blasting cap needs more than 25 milliamps to fire it off you are going to need to use a transistor to fire it.

Also if you read the article the Iraqi freedom fighters used to use the remote control devices for toys to trigger their bombs.

So to prevent some 8 year old from setting off their IEDs or bombs they started putting PIC microprocessors on them so you had to enter a sequence of DTMF digits to set them off.

Raspberry Pi could be used for this

The Raspberry Pi is a series of small single-board computers that could be used for stuff like this.Raspberry Pi are dirt cheap computer boards that run Unix or Linux and could be used for stuff like this.

Parallax BASIC Stamp and Propeller Chip

Parallax IncParallax designs and manufactures two microcontrollers, the BASIC Stamp and Propeller chip.

599 Menlo Drive, Ste.100

Rocklin, CA

95765support@parallax.com

(888)512-1024

The BASIC Stamp, developed in 1992 is widely used by hobbyists, engineers, and students around the world.

The multicore Propeller Chip, our newest chip, is gaining tremendous popularity. It is used in many industries including manufacturing, process control, robotics, automotive and communications.

Propeller Chip

Go multicore with the Propeller chip. This chip features eight 32-bit processors and a shared memory and system clock, making true independent and cooperative simultaneous multi-tasking possible. Developer has full control over how and when each cog is employed; there is no compiler-driven or operating system-driven splitting of tasks among multiple cogs. A shared system clock keeps each cog on the same time reference, allowing for true deterministic timing and synchronization. Users appreciate the overall processing power, I/O capabilities, on-board video generation, parallel processing, easy connections to popular PC peripherals and more.

The Propeller chip is a multicore microcontroller that is programmable in high-level languages Blockly, C, and Spin, as well as a low-level (Propeller assembly) language. Application development is simplified by using the set of pre-built objects for video (NTSC/PAL/VGA), mice, keyboards, LCDs, stepper motors and sensors.

The Propeller is designed with an emphasis on general-purpose use, with powerful capabilities that are great for customized high-speed embedded processing, while maintaining low power, low current consumption and a small physical footprint. The Propeller's processors are all identical, each with its own separate memory, and each with an identical interface to all 32 I/O pins and internal shared memory. The architecture is built for swift processing of asynchronous events, equal access to internal and external resources, and dynamic speed and power when it's needed.

The P8X32A-Q44 is useful for production-level SMT-based circuits. The Propeller is easily connected to your computer's serial or USB port for programming using our Prop Plug. The Propeller chip can run on its own with a 3.3-volt power supply, internal clock, and with its internal RAM for code storage. Add an external EEPROM for non-volatile code storage and an external clock source for accurate timing.

BASIC Stamp

The BASIC Stamp line of microcontrollers was created specifically to make learning to use a μ-controller simple and easy.

A BASIC Stamp is a single-board computer that runs the Parallax PBASIC language interpreter in its microcontroller. Functioning as stand-alone ICs, beginners can plug a BASIC Stamp into a board and immediately begin programming, with no other circuitry required. The enormous amount of information for BASIC Stamps available in print and online make the Stamp line one of the most widely documented μ-controllers in existence.

Circle of Terror: Following the Trail of Deadly IEDs From Arizona to Iraq and Back

h3 align="center">Circle of Terror: Following the Trail of Deadly IEDs From Arizona to Iraq and BackSEAN HOLSTEGE | JUNE 14, 2018

First of two parts.

In March, a jury in the U.S. District Court in Arizona convicted a 40-year-old Syrian man on four terrorism-related counts, stemming from his role during the U.S.-led occupation of Iraq. The conviction capped a violent criminal odyssey that spanned 12 years and four continents.

The Justice Department called the case the first U.S. indictment of a weapon-maker from the Iraq war. Ahmed Alahmedalabdaloklah is scheduled for sentencing in August and faces life in prison.

His conviction brought the story’s Arizona connections full circle. The roadside bombs included parts made in Chandler. They killed more than 1,700 U.S. soldiers, including Ryan Haupt of Phoenix, and maimed thousands more, like Robert Bartlett of Gilbert. Many such bombs in Iraq incorporated

The story is also part of a larger tale still unfolding in U.S. courts about who shares responsibility for these U.S. casualties. Part 1 follows the capture and conviction of the man who designed the bombs. Part 2 examines the role banks played in these tragedies.

CHAPTER 1 : BAGHDAD AND THE INSURGENCY

Mid-morning. August 30, 2006. Baghdad’s Omar Street. A few shops were open along the busy artery that ran through a comfortable neighborhood a mile from the Tigris River.

Across the river, a squad of American GIs rolled out of its base at Baghdad International Airport and made the short trip to this place. But even short trips were never short. Not then, not there. Not with all the bombs.

The troops spilled out of an armored vehicle into the 100-degree heat. They broke the lock on 50 Omar Street, and scaled the stairs to the second-floor apartments.

For Staff Sergeant Todd Wilson, it was just another day. His team with the 423rd Infantry Regiment of the 106th Infantry Division were part of a campaign to clear the entire sprawling city of Baghdad, one building at a time.

“We were looking for specific components,” Wilson later testified in an Arizona courtroom. “Large amounts of cellphones, wiring, soldering equipment, analyzers, things of that nature … we knew were being used to make a device, explosives or anything.”

When he reached the second floor, electronics littered the place. He told his squad to secure the area.

Wilson’s eyes shot to a spectrum analyzer. It sat near a window overlooking the busy street. The military used it as a main supply route. Next to the electronic device laid radios that looked like those U.S. soldiers carried.

In Iraq in 2006, insurgent groups blew up IEDs using radio-controlled devices such as those found on toys, or more commonly, signals from cellphones.

“The spectrum analyzer was significant because it detects frequencies that some of our equipment can use,” Wilson explained. “It would be able to emulate our frequency or interfere with a frequency.”

In Iraq in 2006, insurgent groups blew up IEDs using radio-controlled devices such as those found on toys, or more commonly, signals from cellphones. Specific signals on specific frequencies triggered the detonators. But bombers didn’t want their devices to go off too early or too late, so the transmissions were coded.

The U.S. military took countermeasures to jam those transmissions and thwart bombings. The spectrum analyzer at 50 Omar Street would prevent that.

Wilson immediately called his captain, as his squad stood watch.

Within two hours, a more sophisticated team arrived, led by William Huff, who served four tours in Iraq and retired as a colonel.

In 2006, Huff belonged to the Asymmetric Warfare Group, which studied the methods and tactics of the guerrilla units in Iraq. He led a strike team to systematically collect evidence from places just like 50 Omar Street.

The Army had learned it needed to preserve evidence better to glean vital information, Huff testified in Phoenix.

His team snapped on surgical gloves and looked for secret compartments in the walls, floors — everywhere. They mapped the apartment rooms and coded the GPS location. They captured hundreds of photographs and lifted fingerprints.

They bagged and tagged all the soldering irons, circuit boards, radios, computer equipment, switches, transmitters, receivers, and documents. Huff knew this discovery was important.

It stood out because of “the amount of material that we found on-site and the uniqueness of that material,” Huff testified. In his three years in Iraq, he’d not seen the same level of sophistication.

They took the haul over to Saddam Hussein’s old Ministry of Defense building, where the team bunked each night. There, they spread out all the material on the floor and began cataloging it.

Within two hours of Huff’s team packing up, a bomb ripped through the same Omar Street neighborhood. The explosion killed 24 civilians and injured 35, according to official reports catalogued by the online IntelCenter.

The group listed dozens of attacks that day in Iraq, including five IED explosions.

At that time, nobody in U.S. military, intelligence, or law enforcement circles had ever heard of Ahmed Alahmedalabdaloklah. They didn’t know they were looking for him. Yet.

He slipped away.

On October 17, 2006, Army Staff Sergeant Ryan Haupt of Phoenix rode in convoy in Baqubah, about 40 miles north of the capital, with the 1st Battalion, 68th Armored Division. A roadside bomb erupted under his vehicle. He was killed. He was 24. He had just married before he was deployed to “The Sandbox,” Iraq. Now his young bride, Nannette, was a widow.

The bomb that killed him was an emerging breed troops were finding. After troops added armor to the bottoms of their Humvees, insurgents placed conical copper plates atop their bombs.

The explosions would melt the plates. The heat would drive through the armor and spray shrapnel and molten copper through the cabins of military vehicles, like the one in which Haupt died.

The plates were coming from Iran, military commanders and intelligence reports began noting.

Lance Haupt, a Glendale truck driver and father of the fallen soldier, has sued Iran and some western banks that did business with Iranians.

“I don’t feel good about any of our troops being deployed anywhere. We’re told they are fighting for our freedoms, but they aren’t,” he said in an interview with Phoenix New Times. “It’s so angering to have our military act as missionary to these banks so they can rule the world. They are profiting from the lives and deaths of our children. They are absolutely satanic.”

Fallen Heroes Project

Haupt described his son as headstrong. Ryan grew up in North Hollywood, California. He had reacted badly to his parents’ divorce. After moving to the Phoenix area, Ryan wanted to join the Army at age 17. His father eagerly signed the paperwork. Structure would be good.

“The last time I talked to him, he was in Chicago and decided to get married. I said, ‘Why don’t you have a real wedding and invite the family?’” Haupt recalled.

His son refused. He didn’t want to wait until after his deployment to Iraq, having just returned from South Korea.

Ryan Haupt was part of a three-man sniper team that conducted 200 combat missions together in Iraq. The Baqubah job in October 2006 was its last. All three died.

On the Fallen Heroes Project website, one of his aunts, Carol Lumpkin, said enlisting was the highlight of his life, which had been filled with letdowns. “He overcame all the disappointment and was a man,” she wrote.

Another aunt, Marilyn Haupt-Howald, remembers a happy and fun man, who had been born at 12 pounds with lanky limbs and “the bluest of eyes.”

“Ryan was a truly sweet, fun-hearted person with such a love for laughter, a cousin, Kristina Howald, wrote. “He always made sure that he would get you busting up.”

On April 6, 2007, Good Friday, a U.S. military convoy neared the Baghdad airport when an IED exploded, killing a 19-year-old private named Damian Lopez Rodriguez and two of his Army comrades.

Rodriguez was from Nogales. His high school pals in Tucson asked him why he was going to Iraq. He told them so he could put low-rider rims on the tanks. He was known for his jokes. A teacher told the Arizona Daily Star, “We’ve lost a good one.”

The same day, in another part of the Iraqi capital, another bomb exploded under the vehicle carrying another 19-year-old, Daniel Fuentes of New York.

Fuentes’ parents also joined the class-action lawsuit against the banks, because the device had the hallmarks of an Iranian-made weapon.

By 2007, U.S. officials were better at finding clues amid the smoking rubble. They, along with the British, Australians, and Iraqis, had created Joint Task Force Troy, and assigned nearly 900 military and civilian personnel to its mission: Stamp out the IED threat.

One of its units was called the Combined Explosive Exploitation Cell, known better as CEXC, or the “Sexy Team.” It comprised military bomb experts, as well as FBI and U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives agents.

The unit’s job was to rush to a bombing and glean as much forensic evidence as possible. From it, they could pinpoint the bomb and its controlling devices and maybe also the bomb-makers and insurgent group that planted it.

They had to recover evidence quickly. It was a war zone. They couldn’t be as meticulous as they would at a crime scene back home. Insurgents targeted the initial responders to attacks with secondary attacks of mortars and sniper fire.

With CEXC’s analysis, the military could target an insurgent group, and federal agents could start developing a criminal case.

By now, the FBI had set up a new nerve center in Quantico focused on diffusing the bomb threat. The Bureau established the Terrorist Explosive Device Analytical Center, or TEDAC, in 2003.

The Omar Street cache went there. Now, seven months later, the CEXC team was poring over a crater near Baghdad’s airport, where Damian Rodriguez with his unit from the 18th Infantry Regiment, 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 1st Infantry Division had just died.

The Sexy Team found something. The circuit boards and transmission devices resembled closely, if not perfectly, those CEXC had analyzed from Omar Street, federal agents later claimed.

A month later, another IED blew up a half-mile from Omar Street, killing one U.S. soldier. They found the same electronics in that bomb.

The parts came from everyday devices — cellphones, radios, remote-controlled toy cars, key fobs, garage door openers, robot vacuum cleaners. TEDAC, CEXC, and their military counterparts knew they were being adapted for roadside bombs.

And they knew each design, each combination of components and circuits, was like a bomb-designer’s fingerprint.

One telltale was the use of technology that enabled push-button telephones, and much later, cellphones. When you push the buttons, something has to tell the phone to dial the right number.

“Without encryption, anybody could deliberately or accidentally blow up any bomb. You didn’t want to blow yourself up or be blown up, so you need something to distinguish the signals.”

That’s done by a microchip on an integrated circuit board, which creates a coded dual-tone multi-frequency, or DTMF. This was how insurgents told IEDs to go off. Wrong code, wrong frequency — no explosion.

“Without encryption, anybody could deliberately or accidentally blow up any bomb,” said one ATF agent familiar with IEDs in Iraq, who spoke on condition of anonymity because of ongoing investigations. “You didn’t want to blow yourself up or be blown up, so you need something to distinguish the signals.”

That something is DTMF.

As the military developed countermeasures to neutralize the signals, Iraqi insurgents came up with new systems. The military began assigning labels: DTMF-1 for the first generation, DTMF-2 for the second, and so on. By 2006, they were seeing DTMF-11 devices.

The soldiers found DTMF-11 devices found on Omar Street and in the craters nearby and at the airport the next year.

These bombings had the electrical engineering fingerprint of Alahmedalabdaloklah, the U.S. government claimed.

But the FBI had something else. The man’s real fingerprints. Agents later testified 26 of the man’s confirmed prints matched those lifted on Omar Street from electric tape, notebooks, and a manual on how to assemble the electronics to power an IED.

Alahmedalabdaloklah was designing DTMF-11 systems, agents said.

The manhunt was on.

The bombings just continued. Day upon day. Relentlessly.

In 2007, U.S. forces caught a major break.

They were investigating a brazen attack in Karbala. Insurgents, posing as allies, got into a U.S. base, lobbed grenades, captured four soldiers, and killed them as they fled across the Euphrates River.

Two months later, on March 20, 2007, coalition forces captured two of the masterminds. One was a Hezbollah leader named Ali Musa Daqduq.

He was found with a 22-page memo detailing the plans for the attack and who approved it. He also kept a journal, which logged IED attacks and described coordination with other factions, whom the U.S. collectively called the Iraqi Special Groups.

The U.S. government claimed Daqduq “was in Iraq working as a surrogate for Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps Quds Force operatives involved with special groups.”

The Quds Force is an elite unit within the Iranian Revolutionary Guard. It was tasked with exporting the Islamic Revolution by supporting proxy wars like Iraq’s conflict.

U.S. forces had a year earlier seized the Quds Force’s third highest-ranking commander. He detailed for his captors “the import of sophisticated weaponry from Iran to Iraq.”

American officials said Daqduq admitted he worked with Quds leaders to plan and train for the Karbala attack, and that spy satellites spotted a training center near Qom, Iran, which contained a mockup of the U.S. base.

The U.S. said it now knew that Iranian-made IEDs were killing its soldiers in Iraq, that Iran’s crack paramilitary unit had trained insurgents fighting in Iraq, and that Iranian money being laundered through western banks was helping pay for it.

In October 2007, the U.S. government declared the Quds Force a terrorist organization.

CHAPTER 2 : THE MANHUNT SHIFTS TO PHOENIX

By 2007, as the FBI’s bomb lab TEDAC sifted through bomb parts, Ahmed Alahmedalabdaloklah, the suspected IED engineer, had long since fled Iraq, through Syria, to China. Now, federal agents were on the man’s trail, and part of that trail led back to Arizona. The FBI shifted its probe to Phoenix.

In January 2010, the FBI entered the Syrian’s fingerprints into its database and matched them to the Omar Street electronics workshop.

FBI Special Agent Dina McCarthy, a former Army intel officer, was now working in the Bureau’s Phoenix field office. She began poring over the Baghdad evidence to trace Alahmedalabdaloklah, who went by numerous aliases, including Ahmad Al-Ahmad.

McCarthy told a federal judge in Arizona in an affidavit she suspected Al-Ahmad of supporting terrorists. The court sealed her statement and the government pursued the Syrian in secret.

“Numerous documents found at Al-Ahmad’s residence clearly indicate that Al-Ahmad was interested in improving the functionality of his IED designs by incorporating innovative technologies and advanced electronic components,” McCarthy later swore in a new affidavit.

The government described 50 Omar Street as one of the biggest and most significant troves of evidence ever recovered during the Iraq conflict.

“Without his technology, without his advancing the technology, their devices would not have been as effective as they were,” said the ATF agent familiar with the case.

In early 2010, Phoenix FBI agents got a court order to access three email accounts used by Alahmedalabdaloklah.

The FBI teamed up with something called Task Force Quiet Storm. The task force paired the Army’s National Ground Intelligence Center and the Department of Commerce. The group targeted foreign IED networks and investigated how they procured adaptable technology with export restrictions.

The FBI looked at a string of emails from 2008 and 2009. In them, Alahmedalabdaloklah discussed orders, procurements, invoices and shipments of cellphones, circuit boards, signal-jamming devices, magnets, and other devices. Many were turning up at bombing sites in Iraq.

In April 2010, coalition forces picked up the man as part of an operation against a leader of the 1920 Revolutionary Brigades.

The 1920 Revolutionary Brigades formed after the U.S.-led invasion and took its name from a revolt against British occupation 80 years earlier. It was composed of Sunni Muslims, many part of Saddam’s regime.

The Sunni faction and the Shiite-dominated Iraq Special Forces were hostile toward each other. But they shared a foe: the United States and its occupying forces.

The 1920 Brigades claimed responsibility in online publicity material for about 230 IED attacks on U.S. forces, the FBI said in court.

Improvised bombs killed 43 Arizona soldiers, nearly half of the state’s 99 military fatalities in Iraq, according to a New Times analysis of data compiled by iCasualties.org from the Pentagon’s monthly reports. Among U.S. forces, 1,721, or nearly 40 percent, died in IED attacks.

In July 2010, the FBI got another break, when forces captured a man called Muhammad Husayn ‘Ali Ways, a relative of the wanted 1920 Brigades leader.

Ways identified Al-Ahmad to FBI agents from a photo. He told them Alahmedalabdaloklah was a member of the Brigade and had fled with his wife and child.

He had introduced Alahmedalabdaloklah to Brigades leaders in 2005 or 2006, and afterward Alahmedalabdaloklah confided to him he “would do anything against Americans.” Ways told the FBI he knew the Syrian was designing DTMF boards to trigger IEDs for the Brigades.

“Ways described Al-Ahmad (Alahmedalabdaloklah) as wealthy, greedy, private, and not trusting of anyone,” as someone who sold the IED components only for the money, the FBI said.

The Bureau noted that Ways had contacted Alahmedalabdaloklah days before his arrest. He warned the exile the U.S. was looking for him and had captured the Brigades leader who paid him for IED parts.

In November 2008, Alahmedalabdaloklah swapped emails with an Iraqi named Jamal Al-Dhari. Al-Dhari’s uncle funded and helped the 1920 Brigades, Interpol said. The U.S. Treasury Department blacklisted the man, claiming he was providing material support to al-Qaida in Iraq.

In one email, Al-Dhari and Alahmedalabdaloklah discussed sending 10 transmitters and 100 receivers to Iraq. In another, Alahmedalabdaloklah told him he could send magnets from China by boat. Iraqi insurgents were using them to affix bombs to car chassis.

Al-Dhari would play an intriguing role when the case went to trial.

Meanwhile, the work at Quantico bore fruit, too. The experts at TEDAC, the FBI’s counter-bomb center, had sifted through the Omar Street evidence.

It included diagrams and technical notes on how to incorporate a Microchip PIC l6F84A and a DTMF decoder chip in bomb electronics.

“This design is typical of many IED circuits employed in Iraq,” the FBI swore in court.

A Chandler company, Microchip Technology Inc., produced all the microcontroller and semiconductors with “PIC” in the model number.

Now the FBI had jurisdiction, a reason to try Alahmedalabdaloklah in Arizona.

The CEXC teams had found IEDs using semiconductors from a New Hampshire company. By now, the Microchip PICI6F84A was showing up in radio-controlled IEDs, the FBI said, attributing the shift “to research done by Al-Ahmad (Alahmedalabdaloklah).”

The Chandler company was blindsided.

“Microchip Technology is appalled by the possible use of our products in such activities. Microchip continues to actively assist government agencies responsible for tracking down and closing supply lines to these entities. Microchip is prohibited from interviews or further statements on this matter,” the company’s public relations manager, Eric Lawson said in an email after the indictment was unsealed.

He did not return a request to comment for this story.

Federal prosecutors first charged Alahmedalabdaloklah under seal on May 10, 2011. But they still didn’t have their man.

Eight days later, Interpol issued a Red Notice saying Alahmedalabdaloklah was wanted for prosecution in the United States on terrorism charges. The same day, Turkish authorities seized him at Istanbul Ataturk Airport as he stepped off an Emirates Airlines plane from China.

Interpol described Alahmedalabdaloklah as a businessman and an engineer with seven aliases and three birthdates. He spoke Arabic, English, and Chinese, and had dealings in Iraq, Syria, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Yemen, Turkey, Malaysia, and Thailand.

The FBI said his Chinese export business processed orders for clients in in Iraq, Syria, Sudan, and Yemen, all terrorism hot spots.

Over the next two weeks, a Turkish lower court ordered he remain in jail. He appealed, lost, and set off a protracted extradition battle.

He languished in Turkish custody, as his case worked its way through the courts to the country’s supreme court and Council of Ministers. Alahmedalabdaloklah lost every appeal. When the U.S. Justice Department added charges to the indictment, the process began anew.

In March 2013, Alahmedalabdaloklah entered a hunger strike to protest the delays from the Council of Ministers. A month later he gave up, ended the hunger strike, and accepted a lower court ruling to extradite him.

But the delays continued, and a top Justice Department official had to fly to Turkey to help the diplomatic corps resolve them.

Finally in June 2014, the Turkish Ministry of Justice notified the U.S. that the Council of Ministers had agreed to extradite Alahmedalabdaloklah.

He was turned over to the U.S. embassy in Ankara on August 27, 2014, three years after his arrest.

Getting Alahmedalabdaloklah to Arizona to stand trial only began his legal odyssey. He spent as long in an undisclosed U.S. cell awaiting trial as he did in a Turkish one awaiting extradition.

From the beginning, the drawn-out legal battle was confrontational.

His first courtroom appearance, in September 2014, lasted just two minutes. That was enough for defense attorneys to demand the U.S. District Court in Arizona refer to him by the name on his passport, not his indictment.

Alahmedalabdaloklah pleaded not guilty on all six charges.

After dozens of defense motions failed to get the case or individual charges thrown out, it inched toward a trial date in early 2018.

Alahmedalabdaloklah’s attorneys sought to bar evidence from detainees, emails, and bomb sites. They sought to curb the use of incendiary words such as terrorist or jihadist, and prevailed.

Defense attorneys had other successes.

They tried to block soldiers testifying about those two fatal explosions in 2007, near Omar Street and the airport. The FBI linked the devices to the Syrian defendant.

Prosecutors argued the bombings were relevant because they were only trying to prove conspiracy to use IEDs, and the types of electronics found in the bomb craters were only found in IED attacks.

The government had consistently said the DTMF-11 components were a “match” or “almost identical” to those found on Omar Street. But now they were saying they were merely “very similar.”

“It is difficult to imagine more powerfully prejudicial testimony than testimony about the deaths of U.S. soldiers. The government evidently intends to introduce this evidence without … producing any evidence showing he is responsible for them.”

Defense attorneys argued that prosecutors were “walking away” from their claims that Alahmedalabdaloklah contributed to the bombings.

“It is difficult to imagine more powerfully prejudicial testimony than testimony about the deaths of U.S. soldiers,” the defense argued. “The government evidently intends to introduce this evidence without … producing any evidence showing he is responsible for them.”

The federal judge agreed, having expressed concern that a mistrial could result from inflammatory evidence that doesn’t “connect up” to the defendant. “I don’t want any mistrials here,” U.S. District Court Judge Roslyn Silver said.

Prosecutors now said they wanted to use the forensic evidence from the explosions to show that “custom-made DTMF-11 boards like those found at Omar Street and on April 6 and May 14” in 2007 were used exclusively to control IEDs.

They argued that the soldiers’ testimony was not “unfairly” prejudicial.

Judge Silver ruled soldiers could not testify about their injuries or experiences in the bombings, only about the authenticity of the circuit boards they found there.

The ruling influenced the outcome.

During discovery, it came out that CEXC and TEDAC had processed two other large electronics caches, and recovered DTMF boards and other components consistent with bombings.

“The use of DTMF-11s in IEDs was pervasive in Iraq. Indeed, the FBI reports that were 381 such circuits found by coalition forces during the time period November 19, 2005, to December 27, 2006, alone, and that of those 381, fully 119 of them were ‘nearly identical’ to boards found at 50 Omar Street,” defense attorneys argued.

“The sheer number of such devices found throughout the country — an average of apparently one a day — makes it implausible that any one person or group of individuals working closely together could be responsible for all of them,” defense lawyers added.

But the proliferation of devices could suggest Alahmedalabdaloklah was the prolific master-designer the government claimed he was. Agents said they found instruction manuals and diagrams he’d left behind. The government said it was “ironic” the defense now brought it up.

Guo Xu told public defenders she wanted to testify to help Alahmedalabdaloklah, but asked to be deposed in Hong Kong instead of mainland China.

Guo Xu told public defenders she wanted to testify to help Alahmedalabdaloklah, but asked to be deposed in Hong Kong instead of mainland China.Court records filed in U.S. District Court in Arizona

The two teams readied themselves for trial.

The defense prepared more than 800 exhibits. Prosecutors amassed almost 1,800 exhibits and readied more than 100 witnesses. The defense readied about 20.

One was U.S. Senator Lindsey Graham, the South Carolina Republican on the Armed Services Committee.

Defense lawyers wanted to know why he met with Jamal Al-Dhari, the nephew of the 1920 Revolution Brigades leader. They also wanted all of the senator’s documents relating to the 1920 Brigades.

The defense asked to subpoena Graham. The judge reluctantly agreed, but advised Graham how to skirt the order. Graham moved to quash it, and the U.S. Senate passed a spot resolution granting him legal support.

Finally, Graham proffered a written statement that he’d met with Al-Dhari in 2017, and left it that. Defense lawyers accepted it.

They were less pleased with the outcome of efforts to bring Alahmedalabdaloklah’s assistant from China.

Guo Xu lived in Guangzhou. She told public defenders she wanted to testify to help Alahmedalabdaloklah, but asked to be deposed in Hong Kong instead of mainland China.

Xu was to tell jurors that the company, Qimitaj, was legitimate. In texts, she told defense lawyers that Qimataj offered home electronics to families. A photo she sent attorneys shows the small shop selling boom boxes, cellphones, and computer accessories.

Then Xu backed out, suddenly.

Prosecutors, who were arranging to travel to Hong Kong, told the public defender’s office that they had no idea why.

It turned out Hong Kong police objected to “the presence of foreign law enforcement officials” and the DOJ’s Office of International Affairs told counterparts of the trip as a routine, but required diplomatic courtesy.

Xu never appeared.

The federal public defender’s office filed a motion to dismiss the case, claiming the government had improperly meddled with a defense witness.

The case went to trial in January. It consumed 23 days in court.

“Ahmed Alahmedalabdaloklah conspired with others to kill military personnel in Iraq using remote-controlled improvised explosive devices. These devices were sophisticated. They included electronics that required technical expertise to operate,” federal prosecutor Joseph Kaster began.

He told the jury how Alahmedalabdaloklah met and got involved with the 1920 Revolution Brigades because they shared the belief that U.S. forces were enemy occupiers.

He had a special skill. He could rig electronic components to transmit signals and set off IEDs, Kaster argued.

He told jurors about 50 Omar Street. “It was an IED switch factory, because it was a place where not just one, not just two, but dozens of these circuit boards for IEDs could be made,” he said.

Kaster deflected the longstanding defense objection, the linkage between 50 Omar Street and the two fatal IED bombings nearby in 2007.

“He’s not charged with the murder of a particular individual on a particular day by placing a bomb on the ground,” Kaster pointed out.

“You’re not going to hear any evidence that any harm ever came to any United States citizen or any piece of United States property as a result of anything that Mr. Oklah did. Not ever,” Facebook Twitter More shares Then-defense attorney Jami Johnson faced the jury, and told them of the omissions.

“You’re not going to hear any evidence that any harm ever came to any United States citizen or any piece of United States property as a result of anything that Mr. Oklah did. Not ever,” Johnson began, deliberately using a Westernized version of the Syrian’s name.

“You’re also not going to hear that anything that Mr. Oklah ever sold or ever touched was ever actually turned into an IED, an improvised explosive device. Nothing,” she continued, adding, “Lastly, you are not going to hear that Mr. Oklah has ever, in his entire life, made a single anti-American statement.”

Johnson told jurors how her client was born in Syria in 1977 and his family fled the murderous dictatorship of Hafez al-Assad, father of the current incumbent.

She described her client as a man, driven by his second-class immigrant status to get ahead, who started an electronics shop to provide for his young family.

He was 25 with a wife and small child when the 2003 war began. Saddam Hussein did not allow cellphones, so a huge market opened after the invasion, and Alahmedalabdaloklah sought to fill it. He had no reason to hate Americans.

As Iraq’s security deteriorated, he decided to relocate his legitimate business to China where he could get cheap parts.

“We’re here as a result of a long series of mistakes, rushes to judgment, and failures to investigate,” Johnson said, turning to the Omar Street discovery.

She said troops incorrectly assumed her client lived there, used the place to make bombs and that those bombs targeted U.S. soldiers. In fact, the documents were school reports and homework, the electronics something typically scavenged in the chaos that ravaged post-invasion Iraq.

“It was this an unfortunate, and ultimately incorrect, snap judgment that then dictated the course of the investigation,” Johnson told jurors. “We’re asking you for the next few weeks to do what the government in this case has not done, which is to keep an open mind.”

One of the first witnesses to take the stand was Jamal Al-Dhari, whose deposition had been recorded in the Latvian capital Riga in 2017. He declined to travel to Arizona to testify.

Al-Dhari was the man with close family ties to the leadership of the 1920 Revolution Brigades, a friend was Saddam Hussein’s ambassador to Russia.

He knew Alahmedalabdaloklah as Mukhtar.

He said he helped get the engineer a passport in 2008 and then communicated with him in China to arrange shipment of 10 transmitters and 100 receivers.

“The resistance were in need for those devices, and they used to use them with bombs to explode them through remote controls,” Al-Dhari testified, explaining they needed more receivers because they get destroyed in the explosions.

“I believe that either Mukhtar (Alahmedalabdaloklah) or the resistance did not commit any crime. It is a right for anybody or any side to resist an invasion or occupation to their country.”

He was unapologetic.

“I believe that either Mukhtar (Alahmedalabdaloklah) or the resistance did not commit any crime,” Al-Dhari testified. “It is a right for anybody or any side to resist an invasion or occupation to their country.”

The FBI first approached him in Riga in June 2016 and “shocked him.” Agents told him they had arrested the Syrian but not why. He assumed it had to do with his role in the resistance, and went to Turkey to try to free him.

The defense said Al-Dhari was not a freedom fighter, but a well-heeled, ambitious man, the kind that can call in favors from the Americans.

“Mr. Al-Dhari is a very wealthy Iraqi citizen who lives in Latvia. Mr. Al-Dhari is a man with political ambitions. He’s not in hiding,” defense attorney Jami Johnson told the jury.

“So why are people who conspire to kill American citizens being invited to the United States to talk to senators and congressmen?” she added.

Al-Dhari testified he met with Graham and U.S. Congressman Ed Royce, a California Republican on the Foreign Affairs Committee. Al-Dhari said he also met with the FBI on four occasions, including twice in Washington, D.C., where he runs a public relations office, but that agents never offered him anything for his testimony.

Then on March 7, prosecutors disclosed he was in the country, 19 days into the trial.

Three court days later, the jury had the case. It deliberated three more.

The panel convicted Alahmedalabdaloklah of the first four counts: conspiracy to use a weapon of mass destruction, conspiracy to destroy U.S. property with an explosive, conspiring to possess a destructive device for a criminal act, and aiding and abetting those who possessed such a device.

Jurors said Alahmedalabdaloklah was not guilty of conspiring to kill Americans abroad or providing material support to terrorists — the two most serious charges.

The defense filed a motion for a retrial, based on “new evidence,” the sudden arrival of Al-Dhari. There has been no ruling.

IF YOU LIKE THIS STORY, CONSIDER SIGNING UP FOR OUR EMAIL NEWSLETTERS. SHOW ME HOW The case against Ahmed Alahmedalabdaloklah, the first of its kind, has sent a warning among U.S. counterterror circles.

“This guy was an international weapons dealer, only instead of sending guns, he shipped circuit boards,” said the ATF agent on condition of anonymity.

“These are sophisticated electronic devices designed to be complex. You really don’t get any sophistication like this anywhere else,” he added. “It’s limitless with cellphones, this technology. That’s the terrifying part.”

Sounds like the Phoenix New Times has sold us out and now supports the military industrial complex.

Just because I am an American doesn't mean I support all the illegal, unconstitutional wars the American government gets involved in. Which includes the current Iraqi and Afghanistan wars and goes back to Vietnam and Korea.

My view is that people like Ahmed Alahmedalabdaloklah are freedom fighters who are fighting the illegal American invasion of their country.

They are not criminals or terrorists as the American government portrays them.

And when they are captured, the American Empire should be jailing them as POWs or Prisoners Of War, not terrorists.

It seems the government is stretching the logic and reason a bit to say that because the Microchip PIC l6F84A chip was made in Arizona, that Ahmed Alahmedalabdaloklah commited Federal crimes in Arizona and can be extradited to the USA and tried in Arizona, simply because the PIC l6F84A chip was used as an IED detonator in Iraq.

And last but not least while the New Times and the FBI are portraying Ahmed Alahmedalabdaloklah as an evil electrical genius and criminal who makes the bomb detonators used by the Iraqi freedom fighters, anybody with a basic background in electronics can make any of those devices.

All of the electrical circuits made in the articles were made with off the shelf chips that anybody can buy.

And anybody with a simple electronics background can read the data sheets and data manuals supplied by the makers of those chips and easily figure out how to make the IED or bomb detonators the Iraqi freedom fighters have been making.

Funding Death: Arizona Families Sue Banks for Financing Iranian Attacks on U.S. Soldiers

SEAN HOLSTEGE | JUNE 19, 2018 | 6:28AM

When Ahmed Alahmedalabdaloklah was convicted on terrorism charges in U.S. District Court in Arizona, the case represented only part of the effort in American courtrooms to hold accountable those who killed more than 1,700 U.S. soldiers with roadside bombs in Iraq.

Federal agents described him as a master bomb-designer during the conflict, and said his case was the first time a foreign combatant from Iraq had been brought to justice in a U.S. court. That was Part 1 of the story.

Part 2 revolves around who paid for those bombs.

The U.S. government went after a string of prominent European banks, accusing them of conspiring to launder hundreds of billions of dollars for Iranian interests, knowing some of that money funded terrorism. The banks paid more than $4 billion in fines to U.S. regulators and admitted responsibility rather than face criminal prosecution.

Based on those actions, dozens of families of killed or wounded soldiers, soldiers like Ryan Haupt and Robert Bartlett of Arizona sued those banks and the government of Iran. Those lawsuits have not reached trial yet. This is the story of how they came to be.

CHAPTER ONE: THE EXPLOSION

On May 3, 2005, Sergeant Robert Bartlett of Gilbert rode inside an armored Army Humvee traveling along “Route Pluto” on Baghdad’s northern edge. He was a sniper.

His Army squad headed to its third mission of the day to clear an area of threats. As the Humvee approached a security barrier along the palm-lined road, it slowed.

Nobody saw the man with the radio transmitter.

Just as the Humvee slalomed its way around the barriers, the man with the transmitter pushed a button.

The blast from the 40-pound IED tore through the vehicle with shrapnel, ball bearings, molten copper, and flame. The driver was mutilated and killed instantly. The gunner’s legs were cut to ribbons. Half of Bartlett’s face had been blown off, from his chin to his temple. Ball bearings perforated his lungs, collapsing one.

Time stopped.

Army Sergeant Robert Bartlett of Gilbert was blown up in an IED attack in Baghdad in 2006. The bomb tore off half his face and killed two comrades.

Bartlett regained consciousness when the gunner collapsed onto him. They cradled each other, helpless, waiting to die. The air inside the wrecked Humvee thickened with the reek of diesel and burnt flesh.

A commander had been thrown clear in the blast. He regained consciousness, pried a door open, and tried to crank the motor.

That year, 2005, a Syrian man named Ahmed Alahmedalabdaloklah started designing the electronic components that enabled insurgents to detonate IEDs remotely, a federal jury in Arizona later found. He had a workshop in the heart of Baghdad, on Omar Street.

The Syrian’s signature design, using microchips produced at Microchip Technology Inc., an unwitting Chandler company not far from Bartlett’s home, showed up in Iraq IED blasts until 2009, the government said.

It presented no evidence that the device used to blow up Bartlett’s squad came from the Omar Street workshop. That attack was not part of that case.

Alahmedalabdaloklah was in league with a faction of Sunnis and former Saddam Hussein supporters called the 1920 Revolution Brigades. Bartlett’s squad was patrolling areas that were hotbeds for Shiite insurgents.

But both rival factions shared the goal of killing and driving out foreign occupiers.

In total, IEDs from all factions killed 1,721 U.S. troops, including 43 from Arizona. Overall, nearly 40 percent of troop deaths came from IEDs. Phoenix New Times analyzed data compiled by iCasualties.org from the Pentagon’s monthly reports.

Court records show that in 2006, coalition forces found 381 IED circuit boards, 119 of them just like those on Omar Street.

“The sheer number of such devices,” Alahmedalabdaloklah’s attorneys argued, “makes it implausible that any one person or group of individuals working closely together could be responsible for all of them.”

Plainly, bombs and bomb components were everywhere.

Roadside bombs like these killed hundreds of American soldiers in Iraq.Department of Defense On Good Friday, April 6, 2007, two IEDs went off under U.S. Humvees, both part of the pattern. Both killed 19-year-old Army soldiers on patrol. Each was characteristic of the bombs used variously by Sunni and Shiite factions.

That month was the third-deadliest of the war for IED attacks. The next month was the worst.

One attack killed Damian Lopez Rodriguez of Tucson and two of his Army comrades. The bomb blew up under a U.S. military convoy near Baghdad International Airport.

FBI agents testified that the electronic components in the IED were identical to those produced and designed by Alahmedalabdaloklah in his Omar Street workshop.

In other part of town, the second blast killed Daniel A. Fuentes from New York.

“The weapon used to kill Daniel A. Fuentes was an Iranian-manufactured IED provided to Iranian-funded and -trained terror operatives in Iraq,” Fuentes’ family alleged in one class-action civil case in federal court.

U.S. government regulators and investigators alleged that Iran and its foreign bankers laundered hundreds of billions of dollars, which in turn helped fund bombing operations in Iraq that killed U.S. and coalition forces.

The families of soldiers killed or wounded in 70 Iraq-conflict IED bombings between April 2004 and November 2011 have sued in federal courts. Bartlett’s family joined Fuentes’ among the plaintiffs.

A half-dozen insurgency groups carried out the bombings under the direction, training, and funding of Iranian forces, the U.S. government and plaintiffs said.

The defendants in nine of those cases include the Republic of Iran and such prominent European banks as HSBC; Barclays; Standard Chartered; Lloyd’s TSB Bank; Credit Suisse; Deutsche Bank; the Dutch ABN AMRO and its buyer, the Royal Bank of Scotland; and Credit Lyonnais and its successor, Credit Agricole Investment Bank.

Plaintiffs alleged the European banks conspired with Iranian government and banking officials to transfer Iranian money illegally to U.S. banks and convert it to dollars. They did this, the lawsuits contend, by deliberately hiding the Iranian origins of funds from U.S. financial regulators and manually falsifying records to ensure money would bypass automatic filters to arrive in the banks’ U.S. subsidiaries.

All the while, the banks knew they were skirting U.S. laws that ban business with some Iranian entities or require full disclosure for those transactions that were legal.

European banks, many British, also knew Iran was funneling some of the money toward IED bombings in Iraq and elsewhere, at a time U.S. and British troops were dying in such explosions. Pentagon statistics show 44 British soldiers died in IED attacks in Iraq.

These banks forfeited $4 billion to federal and state regulators after admitting the responsibility in a deception that lasted more than a decade.

The government had wrested regulatory fines. Now, the families of the fallen soldiers are seeking damages.

“I really feel they need to pay for that. If they are truly laundering money, then they’re supporting terrorism, and even if it’s only business, it’s bad business,” Shawn Bartlett, Robert’s brother, told New Times in an interview.

CHAPTER TWO: SUSPICIOUS BANK TRANSACTIONS

In the first two years of the Iraq war, far away from its blood-soaked streets, as forensic teams examined bomb fragments, a very different kind of investigation unfolded in the United States. Financial auditors were starting to understand how insurgents were funding their attacks.

Investigators with the U.S. Treasury and Justice departments, the Federal Reserve, and the state of New York began wondering about suspicious transactions involving a handful of Iranian banks.

They looked into the possibility that U.S. branches of some European banks might be running afoul of the Bank Secrecy Act, the Trading With the Enemies Act, and the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, which authorized the president to freeze the assets of any foreign entity deemed a threat to national security.

Armed with a stack of federal laws and presidential executive orders, the U.S. Treasury Department oversaw its Office of Foreign Assets Control, or OFAC. Routinely, OFAC updates lists such as the Specially Designated Nationals or SDN list. These act to blacklist foreign individuals and institutions from doing business with Americans.

The U.S. government suspects those on the lists of being involved with such international crimes as drug smuggling, human trafficking, war crimes — or supporting terrorism.

The most recent SDN list has 24,563 names, including just over 200 Iranian people and companies.

The Islamic Republic of Iran supported or partly owned many, including Bank Saderat, Bank Melli, Bank Mellat, and Bank Sepah, along with their subsidiaries.

In 2004, the first year after the Iraq invasion, none of these Iranian banks was on the OFAC list.

Regulators started noticing that money that was popping up in U.S. banks could be tied back to Iranian institutions. At that time, it was legal, but banks were required to report the transactions openly. The U.S. government wanted to check if money transfers were being used to launder money for Iranians on the OFAC blacklist.

The first public sign of a problem came in 2004, when the Federal Reserve Bank in New York entered agreements with local branches of two European banks, Standard Chartered and ABN AMRO, a bank headquartered in Amsterdam.

In the ABN AMRO settlement agreement, the Federal Reserve noted “a pattern of previously undisclosed unsafe and unsound practices” in the Dutch bank’s methods to combat money laundering.

U.S. regulators found that before mid-2004, ABN AMRO’s New York branch “processed wire transfers originated by Bank Melli Iran, a financial institution owned or controlled by the Government of Iran.”

ABN AMRO had been involved with Iran since the mid-1990s, according to the civil lawsuits against it and other banks brought by families of fallen U.S. soldiers.

According to the lawsuits, in 1997 the Dutch bank drafted a strategy paper called “Desert Spring” to work with Iran’s central bank and Bank Melli to drum up deposits “from Iranian nationals.”

By 2003, bank officials were claiming in internal emails, “There is no way the payment will get stopped as all NY (the New York branch) ever sees is a bank-to-bank instruction.”

“As a European institution, we do not comply with U.S. sanctions because those sanctions are politically motivated."

The deception worked like this, according to U.S. regulators and the lawsuit allegations.

First, the Iranian banks would transfer money to their subsidiaries in Europe. Then, the Iranian branch banks in Europe would deposit the money in European banks. But the Iranians wanted dollars, so they had to find a way to get the money to U.S. banks and convert it.

Normally, when a foreign deposit or transfer came to a U.S. branch over the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication, or SWIFT system, bankers would note the identity of the sender and recipient on a form, to ensure that nobody on the OFAC blacklist was involved.

But ABN AMRO would process Iranian transactions differently, using a different SWIFT form used for cover payments. These would appear as bank-to-bank transfers from one of the Dutch bank’s branches outside the United States to one in New York. That concealed the identities of the original parties. Bankers were instructed to forward such payments “without mentioning our bank’s name” on the forms, according to lawsuits and regulators.

Internal memos revealed the Dutch bank’s thinking.

“As a European institution, we do not comply with U.S. sanctions because those sanctions are politically motivated,” a bank compliance officer wrote at the Amsterdam head office.

Another in-house memo suggested a distinction between U.S. policy and efforts to curb money laundering and saw an opportunity in helping clients skirt the regulations.

“OFAC is not the Bible for money laundering,” a banker involved with Iran wrote a colleague. “It is a tool of broader U.S. policy.”

British bank Standard Chartered got involved in Iran as early as 1993.

In 1995, the bank’s lawyers advised in a memo that if “SCB London were to ignore OFACs regulations,” and keep its own U.S. banks in the dark, “there is nothing (U.S. regulators) could do.” The memo was stamped “highly confidential & MUST NOT be sent to the U.S.”

In 2001, Iran’s central bank asked Standard Chartered to process the country’s daily oil sales into U.S. dollars. Bank executives called the contract “very prestigious” because they were now Iran’s de facto treasurers.

Bankers were instructed to type a single period, rather than the name of the sender, on line 52 of the SWIFT forms.

“Approximately 60,000 payments related to lran, totaling $250 billion, were eventually processed by SCB as part of the conspiracy,” according to the civil complaints.

By 2003, the year of the Iraq invasion, Standard Chartered noted some competitors were pulling out of Iran for “reputational risk reasons.”

One bank executive warned in an internal memo that sticking with Iran might trigger OFAC action, causing “potential reputational damage.”

The warning went unheeded.

“You f—-ing Americans. Who are you to tell us, the rest of the world, that we’re not going to deal with Iranians?”

Instead, business with the Iranian Bank Saderat had grown so large that Standard Chartered could no longer manually alter the SWIFT documents.

“SCB automated the process by building an electronic repair system with ‘specific repair queues’ for each Iranian client,” the lawsuits allege.

When U.S. regulators came knocking in 2004, the bank agreed to bring in auditors from Deloitte and Touche. Deloitte’s auditor told the bank’s compliance officer of its early findings in an October 2005 email, noting he “watered-down” the original draft because it was “too politically sensitive.”

The next year, New York regulators asked for audit statistics. One internal email revealed more than 2,600 suspect Iranian transactions worth more than $16 billion.

“Faced with the prospect of disclosing billions of dollars in Iranian transactions,” the class-action lawsuit alleges, Standard Chartered executives ordered the New York branch to turn over just four days of data to regulators, “masquerading as a two-year log.”

Standard Chartered was also unrepentant.

“You f—-ing Americans. Who are you to tell us, the rest of the world, that we’re not going to deal with Iranians?” one Standard Chartered executive was quoted by a New York branch officer as saying.

Court documents tell a similar story about other European banks such as HSBC, Barclays, and Credit Suisse.

Those records say that each bank had long-standing relations with the Iranians. Each created its own method to disguise Iranian transactions. Each made it standard practice and acknowledged the effort to skirt OFAC. Many circulated internal memos warning of the pitfalls, but most carried on because the financial rewards were attractive.

HSBC removed references to Iranian entities by entering “one of our clients” on transfer forms and putting transactions in a special “repair queue,” to be forwarded as internal bank transfers. HSBC processed 700 such transactions a day.

HSBC’s chief compliance officer warned in a 2000 email that the effort to avoid OFAC sanctions unacceptably threatened to embarrass the bank. The next year, a bank auditor warned colleagues to heed pending U.S. legislation, “particularly if we are unfortunate enough to process a payment which turns out to be connected to terrorism.”

Barclays bank concealed Iranian deposits by filtering incoming and outgoing payments and, according to one internal memo, by withholding in transfer messages “extraneous information,” such as the identity of Iranian clients.

“To circumvent U.S. legislation, currently route US$ items for sanctioned institutions via unnamed account numbers,” another Barclays memo advised.

Credit Suisse would omit Iranian names and bank ID codes and instead hand-enter “order of a customer” and its own bank codes. About 95 percent of Credit Suisse’s Iranian transactions were handled this way.

After the Iraq invasion, Credit Suisse used coded abbreviations for customers and trained Iranian clients how to avoid OFAC triggers.

“Credit Suisse became one of the main U.S. dollar clearing banks for the Iranian banking system,” the lawsuit said, adding that by 2006 the bank illegally funneled $480 million into U.S. banks to benefit Iranian interests.

The European banks were working with a handful of Iranian banks, and they had come under the scrutiny of the U.S. government too.

In 2006, the U.S. Treasury Department announced it cut off Bank Saderat from all direct and indirect access to the U.S. banking system. The Iranian regime had nationalized Bank Saderat after the Islamic Revolution.

Under Secretary for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence Stuart Levey said Iran had funneled $50 million to Hezbollah through Bank Saderat.

“It is remarkable that Iran has a nine-digit line item in its budget to support terrorism,” Levey said at the time.

A year later, in 2007, the U.S. labeled Bank Saderat a “Specially Designated Global Terrorist” organization and OFAC blacklisted it.

Class-action lawsuits allege that each named European bank, “knew, or was deliberately indifferent,” that it facilitated the transfer of at least $100 million U.S. to insurgency groups acting inside Iraq, under Iran’s guidance.

The suit names conspirators as Bank Saderat, “and other U.S. Specially Designated Nationals such as … Bank Melli Iran, Bank Mellat, and Bank Sepah” and Iran’s central bank.

U.S. military brass said they knew where some of the money went.

In July 2007, a U.S. general told reporters that Iran was sending $3 million a month to fund IED bombings in Iraq.

U.S. officials said, and the class-action lawsuit alleges, that the money went through the Quds Force, an elite unit within the Iranian Revolutionary Guard responsible for supporting allied terrorist groups around the Middle East, including in Iraq.

The Quds Force established Department 2000 to coordinate with Hezbollah in Lebanon.

Hezbollah created Unit 3800 to help Shiites in the Iraq Special Forces, the umbrella term the U.S. assigned to that group of factions. Unit 3800 trained those insurgents in Lebanon and Iran to attack coalition forces in Iraq.

A key figure in that effort was Ali Musa Daqduq, once the bodyguard to Hezbollah’s leader. In 2005, Hezbollah ordered him “to go to Iran and work with the (Quds Force) to train Iran’s proxies in Iraq,” U.S. officials said after capturing him two years later.

CHAPTER THREE: ARIZONA CASUALTIES PILE UP

Two years after the invasion, the bloodshed in Iraq was ramping up, and Iranian-made IEDs were responsible for much of it. A main culprit was an innovation U.S. forces attributed to the Quds Force and Iran.

The military called them EFPs, explosively formed penetrators. Insurgents started topping remote-controlled roadside bombs with conical copper plates. The heat of the bomb blast would melt the copper, and the molten metal could punch a hole through the armor underneath Humvees.

Humvees like the one carrying Robert Bartlett that day in May 2005.

Bartlett’s commander managed to pry open the hatch of the smoldering Humvee. He moved Bartlett to the back seat, put a tourniquet on the gunner’s shredded legs, and cranked the wrecked Humvee’s motor.

It turned over.

“I just started yelling ‘GO! GO! GO!’ That’s all I could get out because my jaw was hanging down by my neck,” Bartlett told American Forces Press Service years later. “With every breath I took, I was losing another breath.” He was lucky he got the chance to tell any story.

By the time he reached Camp Rustimiyah, on the southern outskirts of Baghdad about 15 miles away, Bartlett had stopped breathing. Doctors declared him dead, but used a tracheotomy to resuscitate him. A helicopter flew him north 50 miles to a hospital in Balad, Iraq, where he was revived a second time.

When the military had to decide whom to airlift for further medical treatment to a military hospital in Germany, triage doctors said others had a better chance of surviving.

Instead, Bartlett ended up in Walter Reed Medical Center in Maryland five days after the bombing. There, doctors brought him out of a coma and his vital signs flatlined again. He was medically dead for a third time in a week.

For years, U.S. leaders, including Texas senator and presidential candidate Ted Cruz, claimed Iranian-made EFPs had killed more than 500 U.S. soldiers in Iraq. A declassified Pentagon report in 2015 put the number at 196 during five-and-half-years.

Whatever the figure, the Iranian bombs were pervasive and deadly.

On January 18, 2009, Army Staff Sergeant Roberto Andrade Jr. of Phoenix was killed by an Iranian-style IED.Fallen Heroes Project More Arizona soldiers followed Bartlett’s fate — or worse.

Five months later, on October 5, 2005, Army Specialist Jeremiah Robinson, a 20-year-old from Mesa, was travelling in Baghdad with the 860th Military Police Company of the Arizona Army National Guard.

An Iranian-made IED, also fitted with the deadly copper cap, blew up his Humvee. He died the next day. It was the fifth-bloodiest month of the war for IED fatalities. Such attacks claimed the lives of 57 U.S. soldiers.

Robinson’s father was a sergeant and 20-year veteran in the Chandler Police Department.

“Jeremiah, his mission in life was to be a soldier, to be a copper,” Burt Robinson, told the Arizona Republic soon after his son’s death. “It was his privilege to serve in that war. Unfortunately, we have to pay the ultimate sacrifice. There’s no reason for it. It just is.”

A year later, on October 17, 2006, Army Staff Sergeant Ryan Haupt of Phoenix rode in a convoy in Baqubah, about 40 miles north of Baghdad. A roadside bomb exploded under his vehicle. He was 24, had just gotten married, and now he was dead.

His father, Lance Haupt, a Glendale truck driver blamed international banks for the death, calling their influence on geopolitics “satanic.”

Ryan Haupt was one of 52 U.S. soldiers killed by IEDs that month, the sixth deadliest.

Eight months later, on June 2, 2007, another Iranian copper-tipped IED killed another soldier with Arizona roots.

Army Sergeant Shawn Dressler died 30 minutes after the attack. He was 22. His company with the 1st Battalion, 18th Infantry Regiment was patrolling Baghdad when the bomb went off.

He was one of 58 U.S. soldiers killed that month in an IED attack.

Dressler had already cheated death during his tour of duty. A Kevlar vest saved him when he knocked back with a spray of bullets in the chest. Now, he left behind two parents and a sister in metro Phoenix, and a new bride, according to a memorial published by the Fallen Heroes Project website.

Dressler had met Amanda Bridges during a previous tour of duty in Iraq. She flew out to Germany to marry him six days after she returned home. Dressler died four days after their first anniversary.

After the Army, he wanted to become a cop, a teacher, or a forest ranger.

On January 18, 2009, Army Staff Sergeant Roberto Andrade Jr. was killed by another Iranian-style IED while his Humvee patrolled Baghdad. He was 26.

He was assigned to the 1st Battalion, 66th Armor, 1st Brigade Combat Team, 4th Infantry Division, according to a Military Times account. He enjoyed playing soccer, football, and basketball.

It was his third tour in Iraq, and he was weeks away from returning home to end his service.

“If people asked you which one was he, you would say, ‘He was the one with the smile.’ He was very soft-spoken, but he could command with that smile,” a woman named Vicky Munari told the Associated Press.

Andrade grew up in Phoenix, where his parents still live.

The Andrades, Dresslers, Haupts, Robinsons, and Bartletts all joined the class-action lawsuits seeking damages from the Republic of Iran and the European banks they allege helped move Iranian money.

Army Staff Sergeant Ryan Haupt of Phoenix was killed by an IED in Baqubah in 2006. He was 24. His parents have joined in a suit against several banks they say financed attacks on U.S. soldiers.Fallen Heroes Project

CHAPTER FOUR: RECKONING WITH JUSTICE

As the U.S. Justice Department got closer to bringing in its quarry and getting Syrian bomb designer Ahmed Alahmedalabdaloklah into a federal courtroom in Arizona, it also closed in on the banks that did business with the Iranians.

In 2009, Credit Suisse agreed to pay a $536 million penalty in a deferred prosecution agreement with the DOJ and New York prosecutors. The Justice Department said it was the largest-ever forfeiture for a violation of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act.

Also in 2009, Lloyd’s accepted responsibility for violating U.S. banking regulations and paid a $350 million fine.

In 2010, the DOJ announced in a press release it entered an agreement with the Dutch bank ABN AMRO, then owned by the R*yal B*nk of Sc*tland.

For eight years until 2004, “ABN caused ABN’s U.S. affiliate to file false, misleading, and inaccurate annual reports of blocked property to OFAC,” the government said.

The bank paid a $500 million fine and admitted responsibility in a deferred prosecution agreement of violating the Trading With the Enemy Act and two other federal banking laws.

Three months later, Barclays forfeited $298 million and accepted responsibility for two U.S. banking violations in a deferred prosecution agreement.

In 2012, DOJ officials announced the HSBC bank had entered into a deferred prosecution agreement, admitted to violating U.S. banking and money-laundering laws, and forfeited nearly $1.3 billion.

“The record of dysfunction that prevailed at HSBC for many years was astonishing,” then-Assistant Attorney General Lanny Breuer said at the time.

Federal prosecutor Loretta Lynch, who later became U.S. Attorney General, said at the time it was the biggest-ever fine imposed under the Bank Secrecy Act.

In 2012, Standard Chartered agreed to forfeit $227 million to the DOJ and accept responsibility for violating U.S. banking law. The Justice Department called the bank’s conduct “flagrant.”

In 2014, later New York regulators reopened their investigation of Standard Chartered and fined the bank another $300 million.

In 2015, Deutsche Bank paid a $200 million fine and entered into a consent agreement with the New York Department of Financial Services.

“If you don’t have money, you can’t buy a bomb.”

None of that money went to the families of the fallen soldiers. They sought compensation, but they were really after something resembling justice. They wait.

“We know these cases may take years to finish,” Shawn Dressler’s parents, Cecil and Tonya Dressler of Sun City, wrote in an open letter to the Arizona Republic a year ago.

“An important part of that fight is ensuring more Americans know the truth about Iran and its enablers’ conspiracy to kill American service members in Iraq. Nothing will erase the pain of Shawn’s murder, but nothing will stop us from seeking justice in his name.”

They did not return an email request for an interview.

For Shawn Bartlett, the 41-year-old interior decorator in metro Phoenix and brother of IED casualty Robert Bartlett, any notion of fairness looms.

“Justice? That’s a huge one for me,” he said. “Justice, for now, there really isn’t.

“Getting rid of the funding is the first front-and-center thing on the dash. Not letting banks do this: launder money and support terrorism,” Bartlett explained. “If you don’t have money, you can’t buy a bomb.”

Army Sergeant Robert Bartlett of Gilbert needed 40 reconstructive surgeries after surviving an IED blast in Baghdad in 2006. He was declared dead three times.YouTube via American Society of Plastic Surgeons Robert Bartlett survived. Before the war, he was a gregarious man and bartender at two local Irish pubs. He joined up in 2003 at age 30, feeling he had to do something after the 9/11 attacks and in homage to a family whose members had been in the military since Valley Forge. His father fought in Vietnam, his grandfather in World War II.

He needed 40 surgeries to reconstruct his shattered face and body. He insisted Shawn stay by his side at Walter Reed. The PTSD made him wary of others.

After his first surgery, he was back in the pub, amid welcoming arms. In one weekend, they raised $38,000 to help pay for his medical costs.

And that’s where an old friend introduced him to a woman and asked if he remembered her.

“I said, ‘yes,’ and went over to her and told her she didn’t know it yet, but I was going to kiss her in three months when the swelling in my face went down,” Bartlett told the American Forces Press Service.

The couple went on a date the next day, and he proposed right away. “We’ve been together ever since. I knew after the first week that I wanted to marry her,” he said.

“People ask me if I’d do it all over again, and I say ‘In a freaking heart beat,” Bartlett said in a YouTube interview.

He spent time working at the Veterans Affairs clinic in Gilbert, helping other vets cope with the same PTSD he suffers. He talked about “white-knuckling it” when he drives under an overpass or a lousy driver cuts him off. Those were danger signs in Iraq of a deadly ambush.

When plaintiffs’ lawyers called Shawn Bartlett and told him of the lawsuit, he was stunned.

“It weighed on me. To think about hundreds of millions or billions of dollars is beyond fathomable. It was pretty shocking that’s what was going on and that’s how much money it takes to fund terrorism,” Bartlett said.

His first instinct was to ask his brother. Then the family talked about the litigation and decided it could do some good.

They decided the money would go not to the family but to helping wounded vets, Shawn Bartlett said. “This is the only way I can be of any help.”

He hopes the case will prevent others being wounded like his brother.

In recent years, Robert Bartlett has become an outspoken critic of the international treaty to curb Iran’s nuclear ambitions. He joined Veterans Against the Deal.

In 2015, he gave an interview on Fox News and talked about the bomb that disfigured him and blew off the top of the head of his comrade, Staff Sergeant William Brooks, after whom Bartlett named his son.